Seventeen years before my current career in journalism, I was in music school, performing symphonies with orchestras. One work, Shostakovich’s tenth symphony, haunts me to this day.

Dmitri Shostakovich was one of the most visible Russian composers of the 20th century. Since Joseph Stalin’s Russia censored most outside composers’ works, Shostakovich’s premieres were under government surveillance for most of his career.

To remain under the radar, yet express his true feelings, the composer threaded hidden messages into his music. His tenth symphony, which premiered 70 years ago, is full of Easter eggs. Its hidden melodies were both a clapback to Stalin and a triumph over superstition.

Ninth Symphonies Were Cursed

To understand the drama in Shostakovich’s tenth symphony, we first need a quick music history crash course.

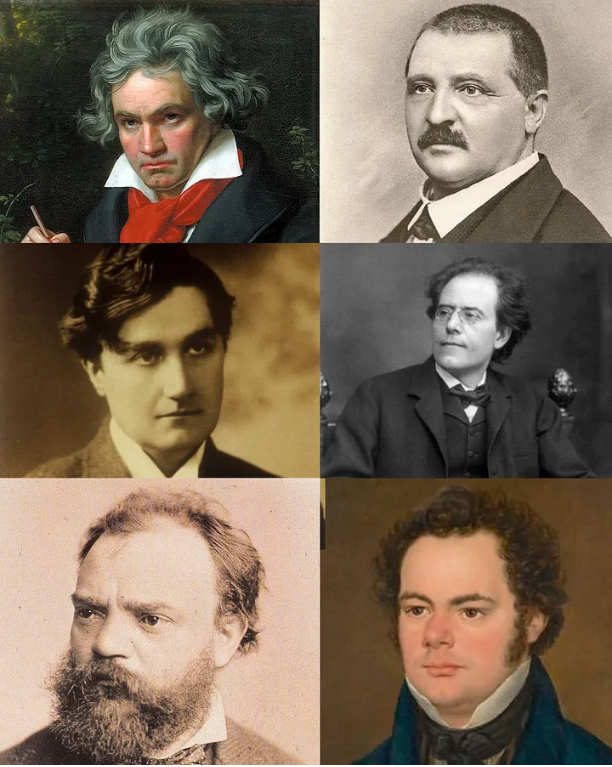

Throughout the 19th century, ninth symphonies were considered epic, but also cursed. Beethoven’s ninth symphony, a 70-minute warhorse, set the bar insanely high — especially considering Beethoven was fully deaf when he wrote it. You may know some of that symphony’s themes from “Ode to Joy”, or Stanley Kubrick’s “A Clockwork Orange.” Beethoven died after writing his ninth.

A bunch of other composers also died after writing their ninth symphonies. Franz Schubert died shortly after finishing his ninth. Antonin Dvořák did, too. So did Ralph Vaughan Williams. Anton Bruckner dropped dead trying to finish his ninth. Gustav Mahler tried to cheat, writing a symphony-length tone poem as his ninth, which seemed to work—but then he died while working on his tenth.

Were epic ninth symphonies cursed?

Perhaps. Shostakovich tried to cheat death a different way: writing a not-so-epic ninth symphony. This really didn’t go over well with Stalin.

The work was censored, being deemed “not reflective of the Soviet Union,” and Stalin publicly boycotted Shostakovich in 1948. Despondent, the composer worked on his tenth symphony in secret for years, waiting until after Stalin’s death in 1953 to premiere it.

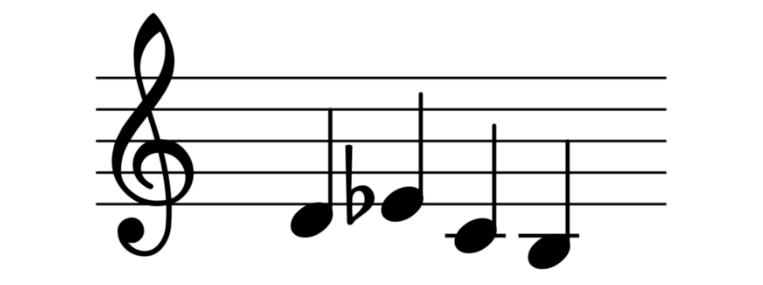

The Secret Solfege Codes

Shostakovich turned his initials into a motif by employing the German solfege syllables D, Es, C, and H. (In German solfege, H refers to B-natural, and B refers to B-flat.) The German spelling of the composer’s name is “Schostakowitsch”, making DSCH appropriate shorthand.

This motif appears all over Shostakovich’s tenth, and other works. The scholarly journal dedicated to Shostakovich research is called the DSCH Journal. DSCH is even on Shostakovich’s tombstone.

Shostakovich was also allegedly in love with a student of his, Elmira Nazirova, an Azerbaijani concert pianist. With similar treatment as his own initials, the composer appears to have etched Elmira’s name into the symphony’s third movement by combining French and German solfege: “E La Mi Re A”.

Musically, the DSCH and Elmira themes appear separately at first, then call and respond, almost as if they’re dancing with one another, never fully intertwining.

Nazirova denied any romantic involvement in a 1990 interview. But she did sit next to Shostakovich at the tenth’s premiere, making it plausible that she was his muse.

Stalin Himself Is Depicted, Too

Rumor has it Shostakovich speed-wrote the remaining second movement after learning of Stalin’s death. According to “Testimony”, a book of memoirs dictated by the composer himself, “The second part, the scherzo, is a musical portrait of Stalin, roughly speaking.” Some of the composition timelines in “Testimony” were disputed by Shostakovich’s peers, so we’ll never know for sure.

Timeline specifics aside, this scherzo is, uh, bananas. It’s fast, pissed off, and an entire show’s worth of notes in about four minutes.

Here’s the legendary 2007 performance of that movement by the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra, with Gustavo Dudamel at the helm, a broadcast that captured global attention. Dudamel was poached by the LA Philharmonic two years later.

Shostakovich’s tenth symphony, performed by the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra (yes, a youth orchestra) in 2007. Video begins at the 27:54 mark, the start of the second movement.

We’ll never truly know what Shostakovich was trying to say. But in times of darkness and despair, reading about the craftsmanship of artists throughout history can help us keep our own creative fire burning bright. ◆

Thanks For Reading 🙏🏼

Keep up the momentum with one or more of these next steps:

📣 Share this post with your network or a friend. Sharing helps spread the word, and posts are formatted to be both easy to read and easy to curate – you'll look savvy and informed.

📲 Hang out with me on another platform. I'm active on Medium, Instagram, and LinkedIn – if you're on any of those, say hello.

📬 Sign up for my free email list. This is where my best, most exclusive and most valuable content gets published. Use any of the signup boxes on the site.

🏕 Up your writing game: Camp Wordsmith® is a content marketing strategy program for small business owners, service providers, and online professionals. Learn more here.

📊 Hire me for consulting. I provide 1-on-1 consultations through my company, Hefty Media Group. We're a certified diversity supplier with the National Gay & Lesbian Chamber of Commerce. Learn more here.